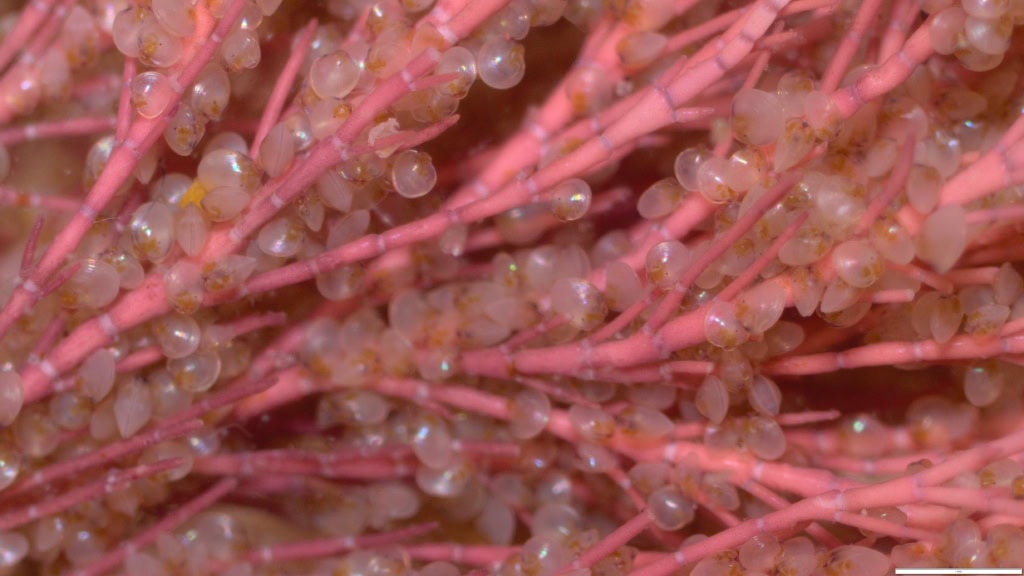

Greenshell™ mussels Perna canaliculus on a farm long-line.

Building the foundations for breeding thermally resilient mussels

Warming waters around New Zealand’s coastline are a concern, especially for Greenshell™ mussel farmers in the upper North Island. Until the early 2000s, the NZ mussel industry relied entirely on wild-collected spat, leaving farmers with little control over growth, survival, or seasonality. Because juvenile supply depended on unpredictable beach-cast events, farm performance was inconsistent and mussels were vulnerable to climatic stressors.

To build resilience, Cawthron Institute, in partnership with industry and government, established Aotearoa’s first structured mussel breeding programme in 2002. Working with SPATnz, BreedCo, and other partners, the programme created the scientific and operational foundation for long-term genetic improvement. With this platform in place and hundreds of selectively bred families developed, we can now research heat tolerance to support breeding for climate resilience and deliver future-ready broodstock.

The Shellfish Aquaculture Research Platform has an established research programme investigating the effects of ocean warming and marine heatwaves on Greenshell™ mussels. With access to ‘family’ lines, ShARP scientists can investigate the genetic basis of heat tolerance. We have developed a chronic heat challenge (exposing mussels to elevated seawater temperatures for several weeks) to test the heritability of heat tolerance. Such tests are widely used in aquaculture around the world. This tool allows us to identify GSM families that are more heat tolerant, enabling farmers to breed from these lines to build resilience.

Testing the genetic basis of heat tolerance

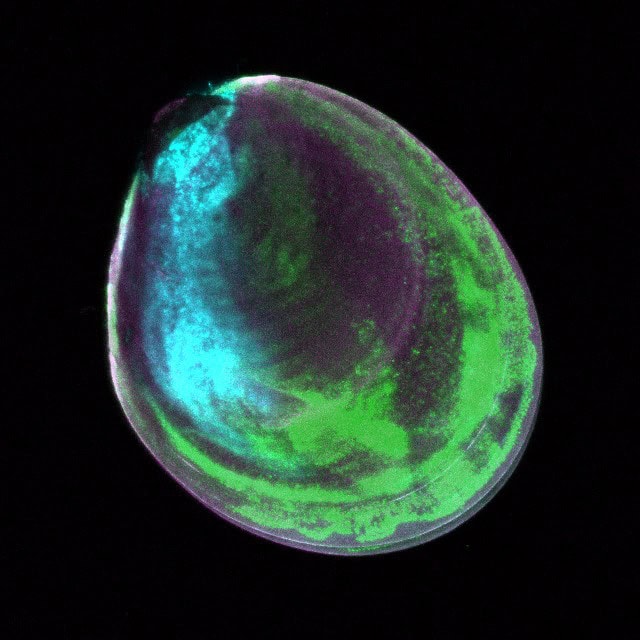

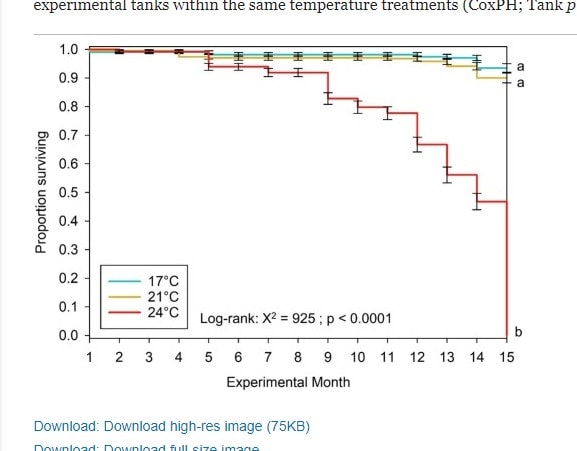

Pilot lab trials showed that for our mussel species Perna canaliculus, 26°C is the best chronic heat-challenge to tease apart differences in family survival. At 24–25°C mussels can survive for months (making trials lengthy and expensive), while at 27°C mortality is rapid and simultaneous, preventing comparisons between families. The maximum sea surface temperature routinely recorded in Northern New Zealand’s coastal waters is 26°C, and is also the temperature threshold where we see an increase in mussel mortalities in land-based facilities (if ponds are not temperature-controlled). Our protocol raises seawater by 1°C per day from ambient to 26°C, holds it there until all mussels die, and uses “time to death” (unresponsive gaping) as the performance measure. Careful definition of the unresponsive endpoint, recording of individual mussel size, and strict tank hygiene are essential.

We have run four trials with two generations of mussel families from SPATnz and Te Huata. Results show strong family-level differences: some mussels die within six days, others last nearly a month. In the field, Coromandel mussel farmers have observed local populations that have endured heatwaves and still continue to produce spat. Thanks to proactive support from Coromandel farmer Peter James, we’ve been able to introduce some of these naturally-selected mussels into our trials. These mussels did well, initially surviving longer than the Marlborough Sounds-derived families, but the selectively-bred families ultimately proved more resilient.

The Cawthron and Te Huata team working on selective breeding of Greenshell™ mussels for improved thermal tolerance

How heritable is heat tolerance in Perna canaliculus?

In each survival trial we calculate heritability to determine what proportion of the variation in survival in the tested population is due to genetics, and what proportion is due to other factors (e.g. environmental factors). Results show genetics play a very significant role in GSM heat tolerance (h² = ranging from 0.26–0.54), meaning selective breeding should improve tolerance over time. For context, heat tolerance in these mussels is substantially more heritable than milk production in dairy cows.

After testing adult families (>60 mm shell length), we used survival data and family information to select and breed the next generation with varying levels of heat tolerance. This new generation were tested as juveniles (average shell length 15mm). These juveniles also showed strong genetic differences, but their heat tolerance did not always match what we expected from their adult relatives. Their biology and priorities differ at this stage, meaning heat tolerance in juveniles and adults could be considered different traits. To unpack this further, we will test the same families again once they reach adult size to see if their heat tolerance aligns better with their adult-tested relatives.

Key questions for future research:

- Can we use simple DNA tests (like a blood sample) to quickly identify mussel families that are naturally more heat tolerant?

- Do mussels carry specific genes that are linked to important traits at different ages, and can we use these genes to guide breeding?

- Is heat tolerance in young mussels the same as in adults, or are they different traits that need to be bred for separately?

- Is a heat tolerant mussel also more resilient to stressors like ocean acidification, low salinity, or disease?

- How does heat tolerance correlate with other traditional breeding traits e.g. growth?

- Is a heat tolerant mussel also more resilient to stressors like ocean acidification, low salinity, or disease?

The path forward: farmer-scientist partnerships for climate resilience

This industry-science partnership has generated novel and valuable insights into breeding for thermal tolerance in GSM, highlighting the strong potential of this species for climate-resilience breeding. While growth traits in shellfish often improve 10–20% per generation, resilience traits like heat tolerance tend to respond more slowly, requiring multiple generations. Focused effort and greater investment would accelerate progress and equip the NZ mussel industry to stay ahead of ocean warming. This requires strong farmer-scientist partnerships and solid collaboration with government, to safeguard our treasured industry feeding Aotearoa and the world.

Farmed Greenshell™ mussels Perna canaliculus

Contact Dr Jessica Ericson

Aquaculture Scientist – Climate change adaptation and outreach, Cawthron Institute

Contact Dr Megan Scholtens

Aquaculture Scientist – Genetics and selective breeding, Cawthron Institute